Growing demands in aerospace, energy, sensors, transport, and bioengineering require high-performance, durable components.

Creating microstructures, such as pits, grooves, pores, dots, and striations, can enhance the surface performance, durability, and functionality of critical components.

Microstructured components are hard to machine, with standard methods including mechanical, EDM, laser, and electrochemical machining.

This paper reviews microstructure processing methods—mechanical, EDM, laser, and electrochemical—and future research directions.

This overview of microstructural processing research may provide new insights for microstructural fabrication methods.

Mechanical Processing

Mechanical processing removes tiny material using micro-grinding and micro-milling.

Experts created microgrooves on Cr12MoV, with a groove area of 37.5% and a spacing of 27.5 μm, resulting in low friction and high wear resistance.

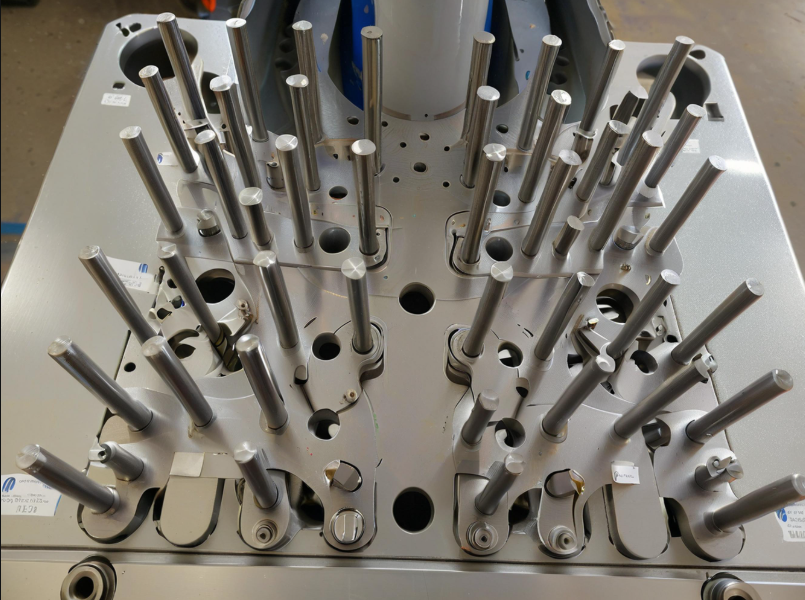

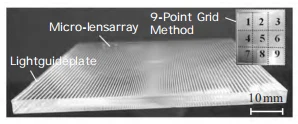

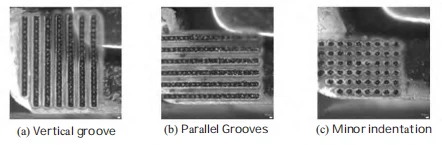

Experts ground micro-grooves on a PMMA light guide plate (Fig. 1), with an average depth of 102 μm. Milling studies revealed that spindle speed and axial depth had the most significant impact on burr height.

A response surface model and particle swarm optimization enabled high-quality milling of curved thin-walled structures (Fig. 2).

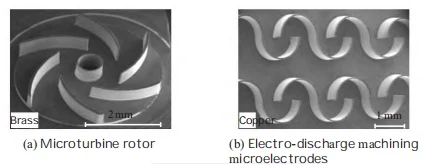

(b) Microelectrode produced by electrical discharge machining (a) Microturbine disc

Precision grinding uses shaped wheels or rods to micro-grind surfaces, offering simplicity and material flexibility.

At the micrometer scale, the tool edge aligns with the cutting thickness, resulting in high stress and wear.

Micro-milling creates precise, flexible, and complex 3D microstructures by guiding cutters along set paths.

Its accuracy is limited by cutter precision, and rounded tool tips produce rounded corners in right-angle structures.

Laser Processing

Laser processing focuses a high-energy beam on the material, causing melting, vaporization, or phase changes to machine the surface.

This technology offers efficient, versatile, and highly controllable processing for both metals and non-metals, enabling a wide range of applications.

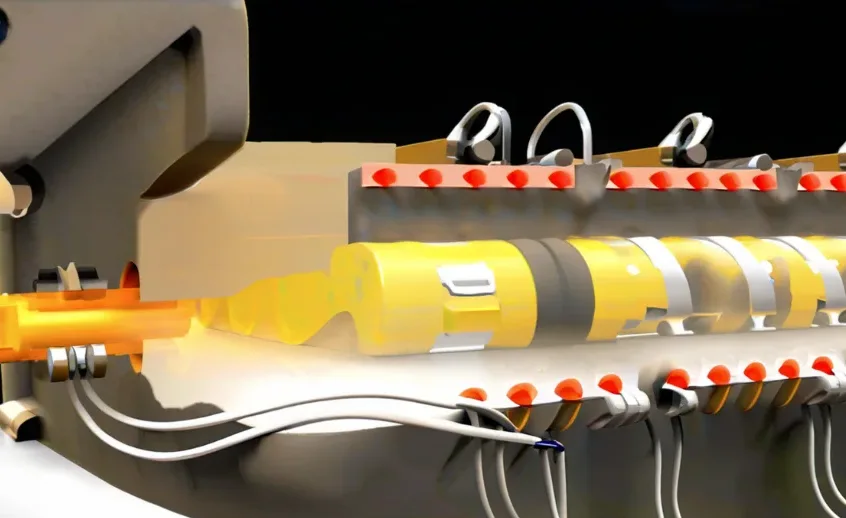

A researcher used laser-processed microstructural rakes on RuT500 milling cutters to study their effect on milling performance (Fig. 3).

Microstructurally reduced cutting forces, improved surface quality, and minimized wear; parallel-edge grooves performed best.

Nanosecond lasers formed microlattices on titanium, thereby enhancing its hydrophobicity and anti-icing properties.

Laser-etched 25 μm × 100 μm microgrooves on WC-8Co reduced friction and improved wear resistance.

Laser processing is precise, versatile, and efficient; however, it can cause thermal defects, necessitating secondary processing to achieve high-quality surfaces.

An in-depth study of laser-material interactions and process optimization is crucial for achieving high-quality, efficient processing.

Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM)

EDM uses pulsed sparks between a tool and a workpiece in a dielectric to erode material.

EDM is non-contact, independent of material hardness, suitable for any conductive material, and ideal for microstructures and complex, hard-to-machine parts.

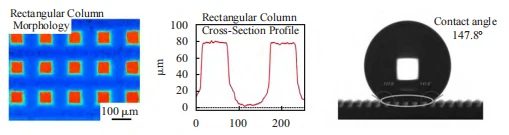

Micro-rectangular pillars on magnesium alloy (75 μm deep, 64 μm wide, 100 μm spacing, 0.854 μm roughness) exhibited superhydrophobicity (Fig. 4).

Using emulsion as the working fluid, micro-rotary EDM produced a 78 μm wide, 6.4 aspect ratio microgroove on stainless steel at 60 V and 3000 r/min.

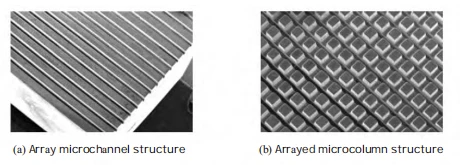

Optimized micro-rotary EDM produced high-quality arrayed microgrooves and columnar structures (Fig. 5).

A study has shown that helical electrodes improve fluid flow and debris removal in microhole EDM, thereby affecting the removal rate, taper, and overcut.

Experiments confirmed helical electrodes produced ~200 μm micro-holes with 12 μm overcut.

EDM can cause recast layers, microcracks, electrode wear, and high tool costs, which affect efficiency and surface quality.

EDM studies often neglect the effects of heat, channeling, and debris; complete erosion and wear models are needed to enhance quality and efficiency.

Electrochemical Machining

Electrochemical machining utilizes the principle of electrochemical anodic dissolution to remove material in ionic form, achieving workpiece processing.

The process avoids tool wear and workpiece stress, making it ideal for precision microstructural machining.

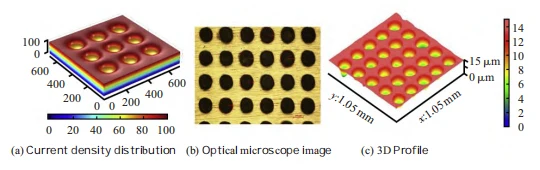

Study the effects of duty cycle and current density on micro-pit arrays, developing a multi-physics electrochemical machining model.

Edge effects are mitigated by adjusting micro-pit spacing, and the current density distribution is optimized.

With 12 s, 12 V, 30% duty, 3000 Hz, and 200 μm mask, a circular micro-pit array of 205 μm diameter and 64.5 μm depth with high surface quality is produced.

Current density simulation-guided mask-electrolytic micro-pitting produced pits ranging from 115 to 160 μm in diameter on stainless steel (Fig. 6).

A response surface model was used to predict micro-pit diameter and depth, which were then validated experimentally.

The moving cathode method corrected edge errors in mask electroforming, as confirmed by both simulation and experiment.

The moving cathode improved uniformity, reducing edge-center depth difference from 14 μm to 6 μm and microgroove unevenness to 68.3%.

The cathode-moving electrolytic machining method enhanced the dimensional uniformity of microgroove array processing.

Electrochemical machining is effective for microstructures; however, complex multi-physical interactions make predicting its performance challenging.

Improving precision and stability requires studying multi-physical field distributions, their interactions, and anodic dissolution theory.

Conclusions

Surface microstructure enhances friction, wear, and hydrophobicity; current machining methods achieve precision, yet challenges persist.

- Mechanical microstructures are less expensive but prone to deformation, burrs, and are limited by machine and tool performance.

- EDM handles high-aspect-ratio structures but suffers from low efficiency, poor surface quality, electrode wear, and high tool costs.

- Laser processing can cause recast layers and heat-affected zones, which reduce quality and risk of microstructural collapse.

- Electrochemical machining provides delicate surfaces, but stray corrosion calls for hybrid processing methods.

Microstructural precision and quality are crucially affected by performance, necessitating further research. Key future directions include:

- Advance microstructural processing by elucidating removal mechanisms, system dynamics, interface modeling, and texture evolution for precise control.

- Refine a physical field model for microstructural machining to reveal parameter effects and guide quality control.

- Analyze the effects of parameters on microstructural accuracy and quality, model factor relationships, and reveal patterns of evolution.

Use AI algorithms to optimize parameters, predict microstructural formation, and achieve high-precision processing.

- Develop intelligent machining inspection methods to replace manual ones, ensuring consistent and efficient evaluation of microstructures.

Use AI, machine vision, and cloud-based analysis for real-time, precise, and consistent microstructure inspection.

- Advance microstructural composite processing by modeling multi-energy interactions to enhance precision, quality, and microstructural formation.

- Develop intelligent, high-performance equipment to enhance the precision and quality of microstructural processing.

Future microstructural equipment R&D should focus on intelligent, high-precision, multi-axis, high-speed, open, networked, composite, and green technologies.

FAQ:

What are microstructures and why are they important in advanced engineering applications?

Microstructures—such as pits, grooves, dots, and striations—enhance surface performance, durability, and functionality of critical components in aerospace, energy, sensors, transport, and bioengineering industries. Proper microtexture design improves friction, wear resistance, hydrophobicity, and overall component lifespan.

Which machining methods are commonly used for creating microstructures?

Key microstructure fabrication methods include mechanical processing (micro-grinding, micro-milling), electrical discharge machining (EDM), laser processing, and electrochemical machining (ECM). Each method has advantages and limitations depending on material type, complexity, and precision requirements.

How does mechanical micro-milling and micro-grinding create microstructures?

Mechanical processing removes tiny amounts of material using micro-milling or micro-grinding tools. It allows precise, flexible shaping of microgrooves and thin-walled components but may cause burrs, deformation, and tool wear at the micrometer scale.

What are the advantages and limitations of laser processing for microtextures?

Laser processing offers high efficiency, precision, and versatility for both metals and non-metals. It can form microgrooves, microlattices, and surface textures, improving wear resistance and hydrophobicity. However, it may introduce thermal defects, recast layers, and requires secondary processing for high-quality surfaces.

How does Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM) help in microstructure fabrication?

EDM uses pulsed sparks to erode conductive materials, enabling complex, high-aspect-ratio microstructures like micro-holes, grooves, and pillars. It avoids mechanical stress but can cause electrode wear, recast layers, micro-cracks, and lower efficiency, requiring careful process optimization.

What makes electrochemical machining (ECM) suitable for precision microstructures?

ECM removes material via electrochemical anodic dissolution, avoiding tool wear and mechanical stress. It produces fine, uniform micro-pits and grooves with high surface quality. Challenges include controlling multi-physical interactions, stray corrosion, and maintaining dimensional uniformity.

How can AI and modeling improve microtexture machining?

AI algorithms and response surface models can optimize machining parameters, predict microstructure formation, and improve precision. Multi-physical field simulations help guide current density, mask design, and tool paths to enhance dimensional accuracy and surface quality.

What are the main challenges in microstructure machining?

Challenges include burr formation, deformation, thermal defects, recast layers, electrode wear, low efficiency, stray corrosion, and limited control over high-aspect-ratio or complex microfeatures. Hybrid and intelligent machining approaches are being developed to address these issues.

How do microtextures affect component performance?

Microtextures reduce friction, enhance wear resistance, improve hydrophobicity, and optimize heat transfer. For tools and precision components, appropriate microstructure design minimizes wear, improves cutting performance, and extends service life.

What are the future directions for microtexture processing research?

Future research focuses on: hybrid processing methods, intelligent and high-precision multi-axis equipment, AI-based parameter optimization, machine-vision inspection, multi-energy composite machining, and green manufacturing technologies to enhance microtexture accuracy, quality, and efficiency.