Compared to machining external cylindrical surfaces, hole machining conditions are significantly less favorable, making hole processing more challenging than external cylindrical machining.

This is due to:

1. The dimensions of tools used for hole machining are constrained by the size of the hole being machined, resulting in poor rigidity and susceptibility to bending deformation and vibration.

2. When using fixed-size tools for hole machining, the hole dimensions often directly depend on the corresponding tool dimensions.

Manufacturing errors and wear in the tool will directly affect the machining accuracy of the hole.

3. During hole machining, chips and heat cannot escape efficiently because the cutting zone lies inside the workpiece.

This makes it difficult to control both machining accuracy and surface finish.

Drilling and Reaming

Drilling

Drilling is the initial process for machining holes in solid materials, typically with diameters less than 80mm.

There are two methods for drilling: one involves rotating the drill bit, while the other involves rotating the workpiece.

The errors produced by these two drilling methods differ.

In drill-rotation drilling, when the drill deviates due to asymmetric cutting edges or insufficient drill rigidity, the centerline of the machined hole may become skewed or non-straight, though the hole diameter remains largely unchanged.

Conversely, in workpiece-rotation drilling, drill deviation causes changes in hole diameter while the hole centerline remains straight.

Common drilling tools include twist drills, center drills, and deep-hole drills, with twist drills being the most widely used, available in diameters ranging from φ0.1 to φ80mm。

Due to structural limitations, drill bits exhibit low bending and torsional stiffness.

Combined with poor centering capability, drilling achieves relatively low precision, typically only reaching IT13 to IT11;

Surface roughness is also relatively high, typically Ra 50–12.5 μm.

However, drilling offers high metal removal rates and cutting efficiency. It is primarily used for holes with lower quality requirements, such as bolt holes, thread pilot holes, and oil holes.

For holes that require higher machining accuracy and surface quality, manufacturers employ subsequent processes such as reaming, boring, or grinding.

Reaming

Reaming involves further processing of holes that have been drilled, cast, or forged using reamers to enlarge the hole diameter and improve machining quality.

Reaming can serve as a pre-finishing operation before precision hole finishing or as the final finishing for holes with less stringent requirements.

Reamers resemble twist drills but feature more cutting edges and lack a cross-edge.

Compared to drilling, reaming exhibits the following characteristics:

(1) Reamers possess multiple cutting edges (3–8 teeth), offering superior guidance and stable cutting action;

(2) The absence of a cross-edge facilitates better cutting conditions;

(3) Smaller machining allowances permit shallower chip flutes and thicker drill cores, enhancing tool body strength and rigidity.

Reaming typically achieves tolerances of IT11 to IT10 and surface roughness Ra of 12.5 to 6.3.

Reaming is commonly used for holes smaller than φ100mm.

When drilling larger diameter holes (D ≥30mm), it is often advisable to pre-drill with a smaller drill bit (diameter 0.5–0.7 times the hole diameter) before reaming with an appropriately sized reamer.

This approach enhances hole quality and production efficiency. In addition to machining cylindrical holes, reaming can also process various countersunk holes and countersink flat surfaces using specialized reamers (also known as countersink drills).

The front end of countersink drills often features guide pins that align with the pre-machined hole.

Reaming

Reaming is one of the finishing methods for holes and is widely used in production.

For smaller holes, reaming is a more economical and practical machining method compared to internal cylindrical grinding and precision boring.

Reamers

Manufacturers generally divide reamers into hand reamers and machine reamers.

Hand reamers feature a straight shank with a longer working section, providing better guidance.

They come in two structures: solid-body and adjustable-diameter. Machine reamers are available in shank-type and sleeve-type structures.

Reamers can process not only circular holes but also tapered holes using taper reamers.

Reaming Process and Applications

Reaming allowance significantly impacts hole quality. Excessive allowance increases reamer load, rapidly blunts cutting edges, hinders achieving smooth surfaces, and compromises dimensional tolerances.

Insufficient allowance fails to remove tool marks from preceding operations, thereby negating quality improvement.

Typically, rough reaming allowances range from 0.35 to 0.15 mm, while finish reaming allowances are 0.15 to 0.05 mm.

To prevent built-up edge formation, reaming is usually performed at lower cutting speeds (v < 8 m/min for high-speed steel reamers machining steel and cast iron).

Feed rate depends on the hole diameter: larger holes require higher feed rates.

For high-speed steel reamers machining steel and cast iron, feed rates are typically 0.3–1 mm/rev.

Adequate cutting fluid must be used during reaming for cooling, lubrication, and chip removal to prevent built-up edge formation and ensure timely chip evacuation.

Compared to grinding and boring, reaming offers higher productivity and easier hole accuracy assurance.

However, reaming cannot correct positional errors in the hole axis; operators must ensure positional accuracy through preceding processes.

Reaming is unsuitable for machining stepped holes or blind holes.

Reamed hole dimensional accuracy typically ranges from IT9 to IT7, with surface roughness Ra generally between 3.2 and 0.8.

For medium-sized holes requiring higher precision (e.g., IT7 accuracy), the drill-ream-tap process is a commonly used standard manufacturing solution.

Boring

Operators enlarge pre-drilled holes using cutting tools in the boring process.

They perform boring operations on either boring machines or lathes.

Boring Methods

There are three distinct methods for boring.

1. Workpiece rotation with tool feed motion This method is commonly used for boring holes on lathes.

Its process characteristics are: the axis of the finished hole aligns with the workpiece’s rotational axis.

The roundness of the hole primarily depends on the rotational accuracy of the machine tool spindle, while axial geometric shape errors mainly depend on the positional accuracy of the tool feed direction relative to the workpiece’s rotational axis.

This method is suitable for holes requiring coaxiality with the outer cylindrical surface.

2. Tool rotation with workpiece feed motion: The boring machine spindle drives the boring tool to rotate, while the worktable moves the workpiece to perform the feed motion.

3. Tool rotation with feed motion: In this boring method, the tool overhang length varies, causing corresponding deformation.

The bore diameter is larger near the headstock and smaller farther from it, forming a tapered hole.

Additionally, as the toolbar overhang increases, the bending deformation of the spindle due to its own weight also increases, causing corresponding bending of the machined hole axis.

This boring method is only suitable for machining relatively short holes.

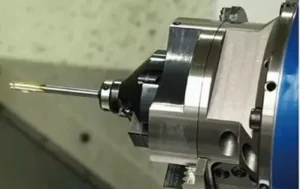

Diamond Boring

Compared to conventional boring, operators perform diamond boring with a shallow depth of cut, low feed rate, and high cutting speed.

It achieves exceptional machining accuracy (IT7 to IT6) and extremely smooth surfaces (Ra 0.4 to 0.05).

Originally performed with diamond boring tools, diamond boring now commonly employs carbide, CBN, and synthetic diamond tools.

Primarily used for non-ferrous metal workpieces, it can also process cast iron and steel components.

Typical cutting parameters for diamond boring are: Feed rate: 0.01–0.14 mm/rev; Cutting speed: 100–250 m/min for cast iron, 150–300 m/min for steel, 300–2000 m/min for non-ferrous metals.

To ensure diamond boring achieves high machining accuracy and surface quality, the machine tool (diamond boring machine) must possess high geometric accuracy and rigidity.

The machine spindle bearings commonly use precision angular contact ball bearings or hydrostatic sliding bearings, and high-speed rotating components require precise balancing.

Additionally, the feed mechanism’s motion must be exceptionally smooth to ensure the worktable performs stable, low-speed feed movements.

Diamond boring offers superior machining quality and high production efficiency, making it widely used in mass production for the final finishing of precision holes such as engine cylinder bores, piston pin holes, and spindle bores in machine tool headstocks.

However, it is important to note: When machining ferrous metal products with diamond boring, only boring tools made of cemented carbide or CBN should be used.

Operators must not use diamond-coated boring tools because the carbon atoms in diamond strongly bond with iron-group elements, which significantly reduces tool life.

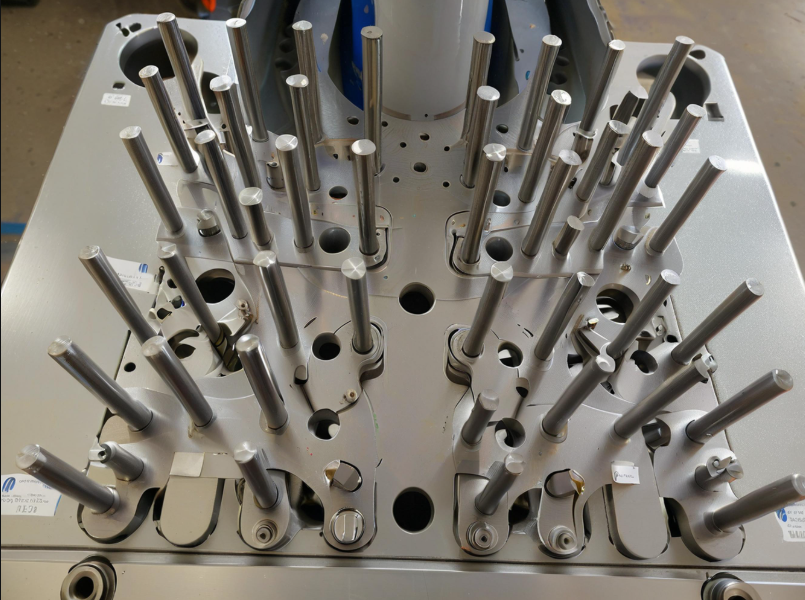

Boring tool

Boring tools can be classified into single-edge boring tools and double-edge boring tools.

Process Characteristics and Applications of Boring

Compared to the drill-ream-tap process, boring is not constrained by tool size limitations.

It possesses strong error correction capabilities, allowing multiple passes to rectify original hole axis deviation errors while maintaining high positional accuracy between the bored hole and locating surfaces.

Compared to external turning, boring suffers from lower rigidity and greater deformation in the tool holder system, along with poor heat dissipation and chip removal conditions.

This results in significant thermal deformation of both workpiece and tool, leading to lower machining quality and production efficiency than external turning.

In summary, boring offers a broad processing range, capable of machining holes of various sizes and precision grades.

For large-diameter holes and hole systems demanding high dimensional and positional accuracy, boring is nearly the only viable method.

Boring achieves machining accuracy grades IT9 to IT7 with surface roughness Ra.

It can be performed on boring machines, lathes, milling machines, and other equipment, offering flexible application and widespread use in production.

Manufacturers commonly use boring jigs in high-volume production to enhance efficiency.

Honed Bores

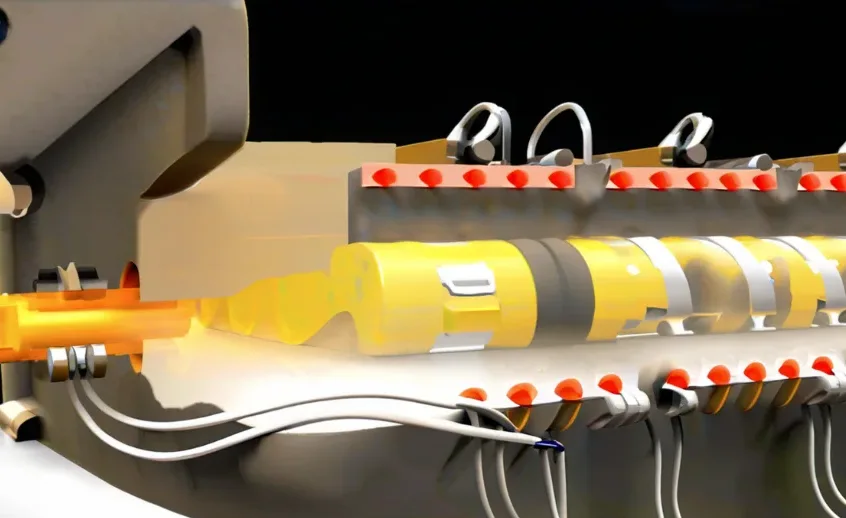

Honing Principle and Honing Heads

Honing is a finishing process that uses a honing head equipped with a honing strip (oilstone) to refine bore surfaces.

During honing, the workpiece remains stationary while the honing head rotates driven by the machine tool spindle and performs reciprocating linear motion.

During honing, the abrasive strip applies a specific pressure to the workpiece surface, removing an extremely thin layer of material. The cutting trajectory forms an intersecting grid pattern.

To prevent overlapping abrasive grain paths, the rotational speed (RPM) of the honing head must be a prime multiple of its reciprocating stroke rate (strokes per minute).

The intersection angle θ of the honing paths relates to the reciprocating speed va and circumferential speed vc of the honing head.

The magnitude of θ affects both machining quality and efficiency. Typically, θ = 40–60° for rough honing and θ = 20–30° for finish honing.

Operators use ample cutting fluid during honing to remove broken abrasive particles and chips, reduce cutting temperatures, and improve machining quality.

To ensure uniform machining of the entire bore wall, the honing strip’s stroke must extend beyond the bore ends by an overtravel amount.

Operators commonly employ a floating connection between the honing head and the machine spindle to ensure uniform honing allowance and reduce the impact of spindle rotational errors on machining accuracy.

Radial expansion adjustment of the honing strip’s grinding strip is achieved through various mechanisms, including manual, pneumatic, and hydraulic systems.

Process Characteristics and Applications of Honing

1. Honing achieves high dimensional and geometric accuracy, with machining precision reaching IT7 to IT6 grades.

Operators can control hole roundness and cylindricity errors within specified ranges, though honing does not improve the machined hole’s positional accuracy.

2. Honing achieves high surface quality with surface roughness Ra ranging from 0.2 to 0.025 μm.

The depth of the surface metal’s altered defect layer is extremely shallow (2.5 to 25 μm).

3. Compared to grinding speeds, the peripheral speed of honing heads is relatively low (vc = 16–60 m/min).

However, due to the large contact area between the honing strip and workpiece, coupled with a relatively high reciprocating speed (va = 8–20 m/min), honing maintains high productivity.

Honing is widely used in mass production for machining precision bores in engine cylinder liners and various hydraulic devices.

The bore diameter range is typically 10 mm or larger, and it can process deep holes with aspect ratios exceeding 10.

However, honing is unsuitable for machining holes in non-ferrous metal workpieces with high plasticity, nor can it process keyway holes, spline holes, etc.

Broaching

Broaching and Broaches

Broaching is a high-productivity finishing method performed on a broaching machine using specially designed broaches.

Broaching machines come in horizontal and vertical types, with horizontal machines being the most common.

During broaching, the broach performs only low-speed linear motion (the primary motion).

Typically, no fewer than three teeth of the broach should engage simultaneously; otherwise, unstable broaching may occur, potentially creating ring-shaped ripples on the workpiece surface.

To prevent excessive broaching forces that could fracture the broach, no more than 6 to 8 teeth should engage at any given time during operation.

Three distinct broaching methods exist, described below:

1. Layer-by-Layer Broaching

This method involves sequentially removing the workpiece’s machining allowance layer by layer.

To facilitate chip breaking, the teeth are ground with interlocking chip-breaking grooves.

Tools designed for layer-by-layer broaching are called standard broaches.

2. Block-Type Broaching

This method involves removing each layer of metal on the machined surface using a group of teeth of similar dimensions but interlocking (typically 2–3 teeth per group).

Each tooth removes only a portion of one layer.Manufacturers call broaches designed for block-type broaching ‘rotary-cut broaches’.

3. Combined Broaching

This method combines the advantages of both layered and segmented broaching.

The roughing section employs segmented broaching, while the finishing section uses layered broaching.

This approach reduces broach length, enhances productivity, and achieves superior surface quality.

Manufacturers call broaches designed for combined broaching ‘combined broaches’.

Process Characteristics and Applications of Hole Reaming

1. Reamers are multi-edge tools capable of sequentially completing roughing, finishing, and honing operations in a single pass, delivering high production efficiency.

2. Reaming accuracy primarily depends on the reamer’s precision.

Under typical conditions, hole accuracy can reach IT9 to IT7, with surface roughness Ra ranging from 6.3 to 1.6 μm.

3.During reaming, operators position the workpiece using the hole itself.(the reamer’s leading edge serves as the locating element).

Reaming does not readily ensure the mutual positional accuracy between the hole and other surfaces.

Operators usually ream holes first in rotary parts needing coaxiality, then use the hole to locate and machine other surfaces.

4. Reamers can process not only circular holes but also shaped holes and spline holes.

5. Reamers are fixed-size tools with complex shapes and high costs, making them unsuitable for large-diameter holes.

Reaming is commonly used in mass production for through holes in small-to-medium parts with diameters ranging from Ф10 to 80 mm and depths not exceeding five times the diameter.

Conclusion

Effective hole machining relies on selecting appropriate methods and tools for the desired precision, surface quality, and production efficiency.

While drilling provides fast material removal for rough holes, reaming, boring, and honing enhance dimensional accuracy and surface finish.

Broaching and combined finishing methods further improve productivity for specialized applications.

By understanding the strengths and limitations of each hole machining process, manufacturers can optimize workflow, ensure consistency, and meet the high standards demanded in modern engineering and mass production environments.

FAQ

What makes hole machining more challenging than external cylindrical machining?

Hole machining is inherently more difficult due to limitations in tool size and rigidity, susceptibility to bending and vibration, and poor chip evacuation and heat dissipation within the cutting zone. These factors affect both machining accuracy and surface finish, making precise hole processing more complex than machining external cylindrical surfaces.

What are the main differences between drilling and reaming?

Drilling is the initial hole-making process, ideal for high material removal rates but offering relatively low precision (IT13–IT11) and rough surface finishes (Ra 50–12.5 μm). Reaming, on the other hand, is a finishing operation that enlarges pre-drilled holes, improving dimensional accuracy (IT11–IT10) and surface quality (Ra 12.5–6.3 μm). Reaming is commonly used for holes smaller than φ100mm and provides superior guidance and stable cutting conditions.

How does boring enhance hole machining accuracy?

Boring enlarges pre-drilled holes and allows correction of original axis deviations. With strong error correction capabilities and flexible application on lathes, boring machines, and milling machines, it achieves high precision (IT9–IT7) and surface finish (Ra). Diamond boring, in particular, delivers extremely smooth surfaces (Ra 0.4–0.05 μm) and tight tolerances (IT7–IT6), making it ideal for precision engine components and mass production.

What is the role of honing in precision hole finishing?

Honing is a finishing process that uses abrasive honing strips to remove a thin material layer, improving hole roundness, cylindricity, and surface quality (Ra 0.2–0.025 μm). It is widely used for engine cylinder liners, hydraulic devices, and deep holes with high aspect ratios. Honing ensures uniform bore surfaces and excellent machining accuracy (IT7–IT6) but does not correct positional errors of the hole axis.

When is broaching used in hole machining?

Broaching is a high-productivity finishing method performed with specialized broaches on horizontal or vertical broaching machines. It efficiently removes material for precision-shaped holes, including keyways and splines. Broaching methods—layer-by-layer, block-type, and combined—offer superior surface quality and high production efficiency, making it suitable for mass production of complex hole geometries.

How do reaming allowances and cutting parameters affect hole quality?

Reaming allowances directly impact dimensional accuracy and surface finish. Excessive allowance increases tool load and reduces surface smoothness, while insufficient allowance fails to remove tool marks. Proper cutting speed (v < 8 m/min for high-speed steel reamers) and feed rate (0.3–1 mm/rev depending on hole diameter) combined with adequate cutting fluid ensure efficient chip evacuation, minimize built-up edge formation, and achieve high-quality holes (IT9–IT7, Ra 3.2–0.8 μm).